Definition

Asthma is a chronic (long-lasting) inflammatory disease of the airways. In those susceptible to asthma, this inflammation causes the airways to spasm and swell periodically so that the airways narrow. The individual then must wheeze or gasp for air. Obstruction to air flow either resolves spontaneously or responds to a wide range of treatments, but continuing inflammation makes the airways hyper-responsive to stimuli such as cold air, exercise, dust mites, pollutants in the air, and even stress and anxiety.

Description

According to the American Lung Association, as of 2007, about 34.1 million Americans, including 9 million children, had been diagnosed with asthma during their lifetime. This number appears to be both increasing, especially among children under age 6, while at the same time the disease is becoming more severe. Asthma is estimated to cause between 3,500 and 5,000 deaths annually in the United States. In 2007, it was responsible for 217,000 emergency room visits and 10.4 million office visits. Its estimated cost to the United States economy is $19.7 billion. Worldwide, asthma is estimated to affect 300 million people. Asthma is closely linked to allergies; about 75% of people with asthma also have allergies.

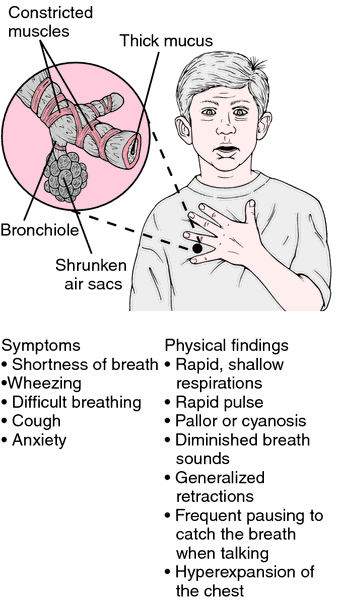

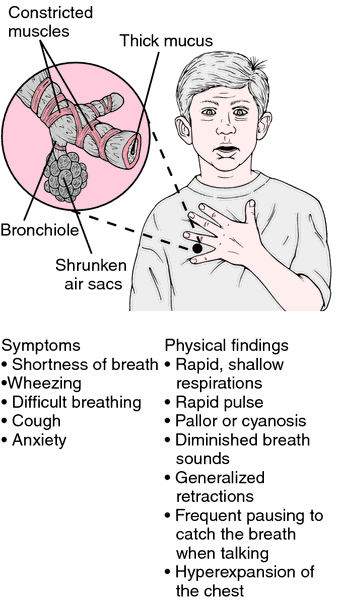

The changes that take place in the lungs of people with asthma makes the airways (the "breathing tubes," or bronchi and the smaller bronchioles) hyper-reactive to many different types of stimuli that do not affect healthy lungs. In an asthma attack, the muscle tissue in the walls of bronchi go into spasm, and the cells lining the airways swell and secrete mucus into the airways. Both these actions cause the bronchi to become narrowed (bronchoconstriction). As a result, an asthmatic person has to make a much greater effort to breathe in air and to expel it.

Cells in the bronchial walls, called mast cells, release certain substances that cause the bronchial muscle to contract and stimulate mucus formation. These substances, which include histamine and a group of chemicals called leukotrienes, also bring white blood cells into the area, which is a key part of the inflammatory response. Many individuals with asthma are prone to react to such "foreign" substances as pollen, house dust mites, or animal dander; these substances are called allergens. On the other hand, asthma affects many individuals who are not allergic in this way.

About two-thirds of all cases of asthma are diagnosed in people under age 18, but asthma also may first appear during adult years. While the symptoms may be similar, certain important aspects of asthma differ in children and adults.

Child-onset asthma

About 9 million American children have been diagnosed with asthma. Approximately 20% of cases begin in the first year of life. When asthma begins in childhood, it often does so in a child who is likely, for genetic reasons, to become sensitized to common allergens in the environment (atopic person). When these children are exposed to dust mites, animal proteins (i.e., animal hair, dander), fungi, or other potential allergens, they produce a type of antibody that is intended to engulf and destroy the foreign materials. This has the effect of making the airway cells sensitive to particular materials. Further exposure can lead rapidly to an asthmatic response. This condition of atopy is present in at least one-third and as many as one-half of the general population.

Adult-onset asthma

Allergies also may play a role when adults become asthmatic. Adults who develop asthma may be exposed to allergens in the workplace, such as certain forms of plastic, solvents, and wood dust. Other adults may be sensitive to aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs such as ibuprofen), or other drugs. More women than men are diagnosed with adult-onset asthma. Compared to childhood-onset asthma, adult-onset asthma tends to be more continuous, while childhood asthma often is marked by asthmatic episodes followed by asthma-free periods.

Exercise-induced asthma

People who may not have allergies can still develop a form of asthma that is brought on by aerobic exercise. These episodes can last for several minutes and leave the individual gasping for breath. Some estimates suggest that 12-15% of Americans are susceptible to exercise-induced asthma. Breathing in cold air, aerobic exercise lasting more than 10 minutes, or shorter periods of very heavy aerobic exercise tend to bring on an exercise-induced asthma attack in susceptible individuals. Polluted air and certain chemicals (e.g., chlorine in pools, herbicides on a playing field) appear to increase the likelihood of an asthma episodes in sensitive individuals.

Causes and symptoms

In most cases, asthma is caused by inhaling an allergen that sets off the chain of biochemical and tissue changes leading to airway inflammation, bronchoconstriction, and wheezing. Avoiding or at least minimizing exposure to asthma triggers is the most effective way of treating asthma, so it is helpful to identify which specific allergen or irritant is causing symptoms in a particular individual. Once asthma is present, symptoms may be triggered or aggravated if the individual also has rhinitis (inflammation of the lining of the nose) or sinusitis (sinus inflammation). When stomach acid passes back up the esophagus (acid reflux), this also may worsen asthma symptoms. A viral infection of the respiratory tract (e.g., a cold) also may trigger or worsen an asthmatic reaction. Aspirin, NSAIDs, and beta-blocker drugs also may worsen the symptoms of asthma.

The most common inhaled allergens that trigger asthma attacks are:

- animal dander

- mites in house dust

- fungi (molds) that grow indoors

- cockroach allergens

- pollen

- chemicals, fumes, or airborne industrial pollutants

- smoke

Inhaling tobacco smoke, either by smoking or being around people who are smoking, can irritate the airways and trigger an asthmatic attack. Air pollutants such as wood smoke can have a similar effect. In addition, three factors that regularly produce attacks in certain asthmatic individuals, and may sometimes be the sole cause of symptoms are:

- inhaling cold air (cold-induced asthma)

- exercise-induced asthma

- stress or a high level of anxiety

Wheezing is often obvious, but mild asthma attacks may be confirmed only when the physician listens to the individual's chest with a stethoscope. Besides wheezing and being short of breath, the individual may cough and/or may report a feeling of "tightness" in the chest. Wheezing is often loudest when the individual breathes out (exhales) in an attempt to expel air through the narrowed airways. Some people with asthma are free of symptoms most of the time but occasionally may have episodes of shortness of breath. Others spend much of their time wheezing or have frequent bouts of shortness of breath until properly treated. Crying or laughing may bring on an attack. Severe episodes often develop when the individual has a viral respiratory tract infection or is exposed to a heavy load of an allergen or irritant (e.g., breathing in smoke from a campfire). Asthma attacks may last only a few minutes or can continue for hours or even days (a condition called status asthmaticus).

Being short of breath may cause an individual to become visibly anxious, sit upright, lean forward, and use the muscles of the neck and chest wall to help move air in and out of the lungs. The individual may be able to say only a few words at a time before stopping to take a breath. Confusion and a bluish tint to the skin are clues that the oxygen supply is seriously low and that emergency treatment is needed. In a severe attack that lasts for an extended period, some of the air sacs in the lung may rupture so that air collects within the chest. This makes it even harder for the lungs to exchange enough air.

Diagnosis

Apart from listening to the individual's chest, the examiner should look for maximum chest expansion while taking in air. Hunched shoulders and contracted neck muscles are other signs of narrowed airways. Nasal polyps or increased amounts of nasal secretions often are noted in asthmatic individuals. Skin changes, such as atopic dermatitis or eczema, are indications that the individual is likely to allergies.

The physician will ask about a family history of asthma or allergies. A diagnosis of asthma may be strongly suggested when typical signs and symptoms are present. A test called spirometry measures how rapidly air is exhaled and how much air is retained in the lungs. Repeating the test after the individual inhales a bronchodilator drug that widens the airways will show whether the airway narrowing is reversible, which is a very typical finding in asthma. Often individuals use a related instrument, called a peak flow meter, to keep track of asthma severity when at home.

It often is difficult to determine what is triggering asthma attacks. Allergy skin testing may be used, although an allergic skin response does not always mean that the allergen being tested is causing the asthma. The body's immune system produces specific antibody to fight off each allergen. Measuring the amount of a specific antibody in the blood may indicate how sensitive the individual is to a particular allergen. If the diagnosis is still in doubt, the individual can inhale a suspect allergen while using a spirometer to detect airway narrowing. Spirometry also can be repeated after a bout of exercise when exercise-induced asthma is suspected. A chest x ray may be done to help rule out other lung disorders.

Treatment

The goals of asthma treatment are to prevent troublesome symptoms, maintain lung function as close to normal as possible, and allow individuals to pursue their normal activities including those requiring exertion. Individuals should periodically be examined and have their lung function measured by spirometry to make sure that treatment goals are being met. The best drug therapy is that which controls asthmatic symptoms while causing few or no side effects. Many people with asthma are treated with a combination of long-acting drugs taken on a regular basis to help prevent asthma attacks and short-acting (quick relief) drugs given by inhaler to reduce the immediate symptoms of an attack.

Drugs

The choice of initial drug treatment often depends on whether the asthma is classified as intermittent, mildly persistent, moderately persistent, or severely persistent, the age of the individual, other medical conditions that may be present, and other drugs the patient may be taking. It make take several attempts to find the best combination of drugs to control the asthma.

Beta-receptor agonists (bronchodilators)

These drugs, which relax the airways, often are the best choice for relieving sudden attacks of asthma and for preventing attacks of exercise-induced asthma. Some bronchodilators, such as albuterol (Ventolin, Proventil) and levalbuterol (Xopenex), act mainly in lung cells and have little effect on other organs. Bronchodilators occasionally may be taken orally (i.e., pills or liquid), but normally they are administered through inhalers. The inhaled drugs go directly into the lungs and cause fewer side effects. These drugs generally start acting within minutes, but their effects last only four to six hours.

Long-acting beta agonists LABAs) have been developed that can last up to 12 hours. These include salmeterol (Severent Diskus), fluticasone/salmeterol (Advair Diskus), arformoterol (Brovana), formoterol (Perforomist, Foradil), and budesonide/formoterol (Symbacort). In January 2008, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning that LABAs may increase the chance of severe asthma episodes and asthma-caused death. LABAs are not recommended as a first-line treatment for asthma. Additional information on these drugs was being gathered at the time this entry was written. The FDA suggests that people taking LABAs discuss the risks and benefits with their physician.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

The leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast (Singulair), zafirlukast (Accolate), and Zyflo (zileuton) control inflammation of the airways by blocking the action of leukotrienes, which are chemicals involved in producing inflammation. These drugs are tablets taken by mouth on a regular basis to treat or prevent symptoms of asthma and exercise-induced asthma. In March 2008, the FDA released a preliminary warning that Singulair might cause behavior and mood changes, suicidal thinking and behavior, and suicide. The warning was preliminary, meaning a cause and effect relationship between these adverse reactions and the drug had not been definitely established, and that more information was needed. The FDA recommended that individuals taking Singulair or any other leukotriene receptor antagonist drug should be alert to these behavioral side effects but not stop taking these drugs until they had discussed their condition with a physician.

Corticosteroids

These drugs, which resemble natural body hormones, block inflammation and are often effective in relieving symptoms of chronic asthma and preventing asthma episodes, but they generally are not used to treat asthma attacks once they have begun. Examples include fluticasone (Flovent), triamcinolone (Azmacort), and beclomethasone (Vanceril, Beclovent, QVAR) all of which are taken by inhalation. When corticosteroids are taken by inhalation over a long time, asthma attacks become less frequent as the airways become less sensitive to allergens. Prendisone (Deltasone, Orasone, Meticorten) is given by mouth (i.e., pills) to speed recovery after treatment of initial symptoms of an asthma attack and sometimes to treat chronic asthma.

Corticosteroids are strong drugs and usually can control even severe cases of asthma over the long term and maintain good lung function. Corticosteroids may cause numerous side effects, however, including bleeding from the stomach, loss of calcium from bones, cataracts in the eye, and a diabetes-like state. Individuals using corticosteroids for lengthy periods also may have problems with wound healing, may gain weight, and may experience psychological problems. In children, growth may be slowed.

Other drugs

Cromolyn (Intal) and nedocromil (Tilade) are anti-inflammatory drugs that affect mast cells. They may be used as initial treatment to prevent asthmatic attacks. They may also prevent attacks when given before exercise or when exposure to an allergen cannot be avoided. To be effective, these drugs must be taken regularly even if there are no asthma symptoms. Anticholinergic drugs, such as atropine, may be useful in controlling severe attacks when added to an inhaled beta-receptor agonist. They help widen the airways and suppress mucus production.

Managing asthmatic attacks

A severe asthma attack should be treated as quickly as possible; professional emergency medical assistance may be needed, as an individual experiencing an acute attack may need to be given extra oxygen. Rarely is it necessary to use a mechanical ventilator to help the individual breathe. An inhaler, usually containing a beta-receptor agonist, is inhaled repeatedly or continuously. If the individual does not respond promptly and completely, a corticosteroid may be given. A course of corticosteroid therapy, given after the attack is over, may make a recurrence less likely.

Many asthma experts recommend a device called a "spacer" to be used along with metered-dose inhalers. The spacer is a tube or bellows-like device held in or around the mouth into which the metered-dose inhaler is puffed. This device enables more medication from a metered-dose inhaler to reach the lungs.

Maintaining control

Long-term asthma treatment is based on inhaling appropriate drugs using a special inhaler that meters the dose. Individuals must be instructed in proper use of an inhaler to be sure that it will deliver the right amount of drug. Once asthma has been controlled for several weeks or months, a physician may recommend that the patient gradually cut down on drug treatment. The last drug added usually is the first to be reduced. Individuals should be seen by their physician every one to six months, or as needed, depending on the frequency of asthma episodes.

School-age and older children may also be prescribed peak flow meters, simple devices which measure how easy or difficult it is for a person to exhale. With home peak-flow monitoring, it is possible for many children with asthma to discern at an early stage that a flare-up is just beginning and adjust their medications appropriately.

Individuals with asthma do best when they have a written action plan to follow if symptoms suddenly become worse. This plan should address how to adjust their medication and when to seek medical help. A 2004 report found that individuals with self-management written action plans had fewer hospitalizations, fewer emergency department visits, and improved lung function. They also had a 70% lower mortality rate.

Referral to an asthma specialist should be considered if:

- a life-threatening asthma attack has occurred or if asthma is severe and persistent

- treatment for three to six months has not met its goals

- some other condition, such as nasal polyps or chronic lung disease, is complicating asthma treatment

- special tests, such as allergy skin testing or an allergen challenge, are needed

- intensive long-term corticosteroid therapy has been needed to control asthma.

Special populations

Infants and young children

It is especially important to closely watch the course of asthma in young individuals. Treatment is cut down when possible, and if there is no clear improvement, treatment should be modified. Asthmatic children often need medication at school to control acute symptoms or to prevent exercise-induced attacks. Parents or guardians of these children should consult the school district on their drug policy in order to assure that a procedure is in place to permit their child to carry an inhaler. The health care provider should write an asthma treatment plan for the child's school. Proper management will usually allow a child to take part in play activities. Only as a last resort should activities be limited.

The elderly

Older persons often have other types of lung disease, such as chronic bronchitis or emphysema. These must be taken into account when treating asthma symptoms. Side effects from beta-receptor agonist drugs (including a speeding heart and tremor) may be more common in older individuals.

Prognosis

More than half of all asthma cases in children resolve by young adulthood, but chronic infection, pollution, cigarette smoke, and chronic allergen exposure are factors which make resolution less likely. Infants and toddlers who have persistent wheezing even without viral infections and those who have a family history of allergies are most likely to continue to have asthma into the school-age years.

Most individuals with asthma respond well once the proper drug or combination of drugs is found, and most asthmatics are able to lead relatively normal, active lives. A few individuals will have progressively more trouble breathing and run a risk of going into respiratory failure, for which they must receive intensive treatment.

Prevention

Minimizing allergy episodes

Exposure to the common allergens and irritants that provoke asthmatic attacks often can be reduced or avoided by implementing the following:

- If the individual is sensitive to a family pet, remove the animal from the home. If this is not acceptable, keep the pet out of the bedroom (with the bedroom door closed), remove carpeting, and keep the animal away upholstered furniture.

- To reduce exposure to dust mites, remove wall-to-wall carpeting, keep humidity low, and use special covers for pillows and mattresses. Reduce the number of stuffed toys and wash them weekly in hot water.

- If cockroach allergen is causing asthma attacks, killing the roaches using poison, traps, or boric acid is preferable to using sprayed pesticides. Avoid leaving food or garbage exposed to discourage re-infestation.

- Keep indoor air clean by vacuuming carpets once or twice a week (with the asthmatic individual absent). Avoid using humidifiers and use air conditioning during warm weather so that windows can be kept closed. Change heating and air conditioning filters regularly. High-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters are available that are very effective in removing allergens from household air.

- Avoid exposure to tobacco or wood smoke.

- Do not exercise outdoors when air pollution levels are high or when air is extremely cold.

- When asthma is related to exposure at work, take all precautions, including wearing a mask and, if necessary, arranging to work in a safer area. Occupational safety and health (OSHA) regulations limit exposure to certain pollutants and potential allergens in the workplace.

Key Terms

- Allergen

- A foreign substance, such as mites in house dust or animal dander which, when inhaled, causes the airways to narrow and produces symptoms of asthma.

- Atopy

- A state that makes persons more likely to develop allergic reactions of any type, including the inflammation and airway narrowing typical of asthma.

- Beta blockers

- Drugs used to treat high blood pressure (hypertension) that limit the activity of epinephrine, a hormone that increases blood pressure.

- Hypersensitivity

- The state where even a tiny amount of allergen can cause the airways to constrict and bring on an asthmatic attack.

- Spirometry

- A test using an instrument called a spirometer that shows how difficult it is for an asthmatic individual to breathe. It is used to determine the severity of asthma and to see how well it is responding to treatment.

For Your Information

Resources

Books

- Allen, Julian Lewis et al. eds.The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Guide to Asthma: How to Help You Child Live a Healthier Life. Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley, 2004.

- "Asthma." United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited January 20, 2009]. http://www.cdc.gov/asthma.

- "Asthma." MedlinePlus. January 16, 2009 [cited January 20, 2009]. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/asthma.html .

- Morris, Michael. "Asthma." eMedicine.com. July 10, 2008 [cited January 20, 2009]. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/296301-overview.

- Allergy and Asthma Network: Mothers of Asthmatics (AANMA). 2751 Prosperity Ave., Suite 150, Fairfax, VA 22031. Telephone: (800) 878-4403. Fax: (703) 573-7794. http://www.aanma.org.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) 555 East Wells Street, Suite 1100, Milwaukee, WI 53202-3823. Telephone: (414) 272-6071. http://www.aaaai.org.

- American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 85 West Algonquin Road, Suite 550, Arlington Heights, IL 60005. Telephone: (847) 427-1200). Email: mail@acaai.org http://www.acaai.org.

Antiasthmatic agents

Allergens

Allergy

Asthma

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

asthma /as·thma/ (az´mah) recurrent attacks of paroxysmal dyspnea, with wheezing due to spasmodic contraction of the bronchi. It is usually either an allergic manifestation (allergic or extrinsic a.) or secondary to a chronic or recurrent condition (intrinsic a.). asthmat´ic

bronchial asthma asthma.

Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers. © 2007 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

asth·ma ( z z m m , ,  s s -) -)

n.

Bronchial asthma.

asth·mat

ic (-m ic (-m t t  k) adj. & n. k) adj. & n. |

asthma

Top: normal bronchiole

Bottom: asthmatic bronchiole

|

The American Heritage® Medical Dictionary Copyright © 2007, 2004 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

asthma

[az′mə]

Etymology: Gk, panting

a

respiratory disorder characterized by recurring episodes of paroxysmal

dyspnea, wheezing on expiration and/or inspiration caused by

constriction of the bronchi, coughing, and viscous mucoid bronchial

secretions. The episodes may be precipitated by inhalation of allergens

or pollutants, infection, cold air, vigorous exercise, or emotional

stress. Treatment may include elimination of the causative agent,

hyposensitization, aerosol or oral bronchodilators, beta-adrenergic

drugs, methylxanthines, cromolyn, leukotriene inhibitors, and short- or

long-term use of corticosteroids. Sedatives and cough suppressants may

be contraindicated. Also called bronchial asthma. See also allergic asthma, asthma in children, exercise-induced asthma, intrinsic asthma, organic dust, status asthmaticus.

Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition. © 2009, Elsevier.

asthma [az´mah]

a condition marked by recurrent attacks of dyspnea, with airway inflammation and wheezing due to spasmodic constriction of the bronchi; it is also known as bronchial asthma.

Attacks vary greatly from occasional periods of wheezing and slight

dyspnea to severe attacks that almost cause suffocation. An acute attack

that lasts for several days is called status asthmaticus; this is a medical emergency that can be fatal. adj., adj asthmat´ic.

Causes. Asthma can be classified into three types according to causative factors. Allergic or atopic asthma (sometimes called extrinsic asthma) is due to an allergy to antigens;

usually the offending allergens are suspended in the air in the form of

pollen, dust, smoke, automobile exhaust, or animal dander. More than

half of the cases of asthma in children and young adults are of this

type. Intrinsic asthma is usually secondary to chronic or

recurrent infections of the bronchi, sinuses, or tonsils and adenoids.

There is evidence that this type develops from a hypersensitivity

to the bacteria or, more commonly, viruses causing the infection.

Attacks can be precipitated by infections, emotional factors, and

exposure to nonspecific irritants. The third type of asthma, mixed, is due to a combination of extrinsic and intrinsic factors.

There is an inherited tendency toward the development of extrinsic asthma. It is related to a hypersensitivity reaction of the immune response. The patient often gives a family medical history that includes allergies of one kind or another and a personal history of allergic disorders. Secondary factors affecting the severity of an attack or triggering its onset include events that produce emotional stress, environmental changes in humidity and temperature, and exposure to noxious fumes or other airborne allergens.

There is an inherited tendency toward the development of extrinsic asthma. It is related to a hypersensitivity reaction of the immune response. The patient often gives a family medical history that includes allergies of one kind or another and a personal history of allergic disorders. Secondary factors affecting the severity of an attack or triggering its onset include events that produce emotional stress, environmental changes in humidity and temperature, and exposure to noxious fumes or other airborne allergens.

Symptoms.

Typically, an attack of asthma is characterized by dyspnea and a

wheezing type of respiration. The patient usually assumes a classic

sitting position, leaning forward so as to use all the accessory muscles

of respiration. The skin is usually pale and moist with perspiration,

but in a severe attack there may be cyanosis of the lips and nailbeds.

In the early stages of the attack coughing may be dry; but as the attack

progresses the cough becomes more productive of a thick, tenacious,

mucoid sputum.

An asthma attack with respiratory distress. From Frazier et al., 2000.

Treatment.

The treatment of extrinsic asthma begins with attempts to determine the

allergens causing the attacks. The cooperation of the patient is needed

to relate onset of attacks with specific environmental substances and

emotional factors that trigger or intensify symptoms. The patient with

nonallergic asthma should avoid infections, nonspecific irritants, such

as cigarette smoke, and other factors that provoke attacks.

Drugs given for the treatment of asthma are primarily used for the relief of symptoms. There is no cure for asthma but the disease can be controlled with an individualized regimen of drug therapy coupled with rest, relaxation, and avoidance of causative factors. Bronchodilators such as epinephrine and aminophylline may be used to enlarge the bronchioles, thus relieving respiratory embarrassment. Other drugs that thin the secretions and help in their ejection (expectorants) may also be prescribed.

The patient with status asthmaticus is very seriously ill and must receive special attention and medication to avoid excessive strain on the heart and severe respiratory difficulties that can be fatal.

Drugs given for the treatment of asthma are primarily used for the relief of symptoms. There is no cure for asthma but the disease can be controlled with an individualized regimen of drug therapy coupled with rest, relaxation, and avoidance of causative factors. Bronchodilators such as epinephrine and aminophylline may be used to enlarge the bronchioles, thus relieving respiratory embarrassment. Other drugs that thin the secretions and help in their ejection (expectorants) may also be prescribed.

The patient with status asthmaticus is very seriously ill and must receive special attention and medication to avoid excessive strain on the heart and severe respiratory difficulties that can be fatal.

Patient Care.

Because asthma is a chronic condition with an irregular pattern of

remissions and exacerbations, education of the patient is essential to

successful treatment. The plan of care must be highly individualized to

meet the needs of the patient and must be designed to encourage active

participation in the prescribed program and in self care. Most patients

welcome the opportunity to learn more about their disorder and ways in

which they can exert some control over the environmental and emotional

events that are likely to precipitate an attack.

Exercises that improve posture are helpful in maintaining good air exchange. Special deep breathing exercises can be taught to the patient so that elasticity and full expansion of lung and bronchial tissues are maintained. (See also lung and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.) Some asthmatic patients have developed a protective breathing pattern that is shallow and ineffective because of a fear that deep breathing will bring on an attack of coughing and wheezing. They will need help in breaking this pattern and learning to breathe deeply and fully expand the bronchi and lungs.

The patient should be encouraged to drink large quantities of fluids unless otherwise contraindicated. The extra fluids are needed to replace those lost during respiratory distress. The increased intake of fluids also can help thin the bronchial secretions so that they are more easily removed by coughing and deep breathing.

The patient should be warned of the hazards of extremes in eating, exercise, and emotional events such as prolonged laughing or crying. The key words are modification and moderation to avoid overtaxing and overstimulating the body systems. Relaxation techniques can be very helpful, especially if the patient can find a method that effectively reduces tension.

Asthmatic patients fare better if they feel that they do have some control over their disease and are not necessarily helpless victims of a debilitating incurable illness. There is no cure for asthma but there are ways in which one can adjust to the illness and minimize its effects.

Exercises that improve posture are helpful in maintaining good air exchange. Special deep breathing exercises can be taught to the patient so that elasticity and full expansion of lung and bronchial tissues are maintained. (See also lung and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.) Some asthmatic patients have developed a protective breathing pattern that is shallow and ineffective because of a fear that deep breathing will bring on an attack of coughing and wheezing. They will need help in breaking this pattern and learning to breathe deeply and fully expand the bronchi and lungs.

The patient should be encouraged to drink large quantities of fluids unless otherwise contraindicated. The extra fluids are needed to replace those lost during respiratory distress. The increased intake of fluids also can help thin the bronchial secretions so that they are more easily removed by coughing and deep breathing.

The patient should be warned of the hazards of extremes in eating, exercise, and emotional events such as prolonged laughing or crying. The key words are modification and moderation to avoid overtaxing and overstimulating the body systems. Relaxation techniques can be very helpful, especially if the patient can find a method that effectively reduces tension.

Asthmatic patients fare better if they feel that they do have some control over their disease and are not necessarily helpless victims of a debilitating incurable illness. There is no cure for asthma but there are ways in which one can adjust to the illness and minimize its effects.

allergic asthma (atopic asthma) that due to an atopic allergy; see asthma.

bronchial asthma asthma.

cardiac asthma a term applied to breathing difficulties due to pulmonary edema in heart disease, such as left ventricular failure.

extrinsic asthma

asthma caused by some factor in the environment, usually atopic in nature.

atopic asthma.

intrinsic asthma that due to a chronic or recurrent infection; see asthma.

occupational asthma extrinsic asthma due to an allergen present in the workplace.

Miller-Keane

Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health,

Seventh Edition. © 2003 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All

rights reserved.

asthma,

n respiratory illness in which constricted bronchi and sticky bronchoid secretions cause wheezing and paroxysmal dyspnea.

Jonas: Mosby's Dictionary of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. (c) 2005, Elsevier.

asthma (az´m

n

a condition characterized by paroxysmal wheezing and difficulty in

breathing resulting from bronchospasms. Frequently has an allergic basis

and occasionally an emotional origin. See also status asthmaticus.

asthma, cardiac,

n

a condition characterized by shortness of breath (paroxysmal dyspnea),

sonorous rales, and expiratory wheezes that resemble bronchial asthma;

related to cardiac failure.

asthma

a condition marked by recurrent attacks of dyspnea, with wheezing due to spasmodic constriction of the bronchi.

It is also known as bronchial asthma. Attacks vary greatly from occasional periods of wheezing and slight dyspnea to severe attacks that almost cause suffocation.

acute equine asthma

sudden

attacks of respiratory distress in horses at pasture; the dyspnea

responds dramatically to treatment with corticosteroids combined with

antihistamines.

allergic asthma

extrinsic asthma; bronchial asthma due to allergy. Called also atopic asthma.

atopic asthma

see allergic asthma (above).

bronchial asthma

asthma.

cardiac asthma

a term applied to breathing difficulties due to pulmonary edema in heart disease, such as left ventricular failure.

feline asthma

see feline bronchial asthma.

Hello everyone! my name is Noah, I'm writing this article to appreciate the good work of DR AKHIGBE that helped me recently to bring back my wife that left me for another man for the past 6 months. After seeing a comment of a woman on the internet testifying of how she was helped by DR AKHIGBE I also decided to contact him for help because all i wanted was for me to get my wife, happiness and to make sure that my child grows up with his mother 'I love my wife' Am happy today that he helped me and i can proudly say that my wife is now with me again and she is now in love with me like never before. Are you in need of any help in your relationship like getting back your man, wife, boyfriend, girlfriend or loves and family relationship. Viewers reading my post that needs the help of DR AKHIGBE should contact him via E-mail: drrealakhigbe@gmail.com You can also call or contact him via whatsapp +2348142454860 He also cure deadly diseases and virus with his natural herbal medicine herbs. like

ReplyDeleteHIV/AIDSHERPESASTHMAEPILEPSYNAUSEA VOMITING OR DIARRHEASTROKEEXTERNAL INFECTIONCANCERDIABETESCHRONIC DISEASEHEPATITIS A&B AND OTHERS. his email again: drrealakhigbe@gmail.comnumber : +2348142454860